The family tree of the Ricasoli family

10 November, 2023

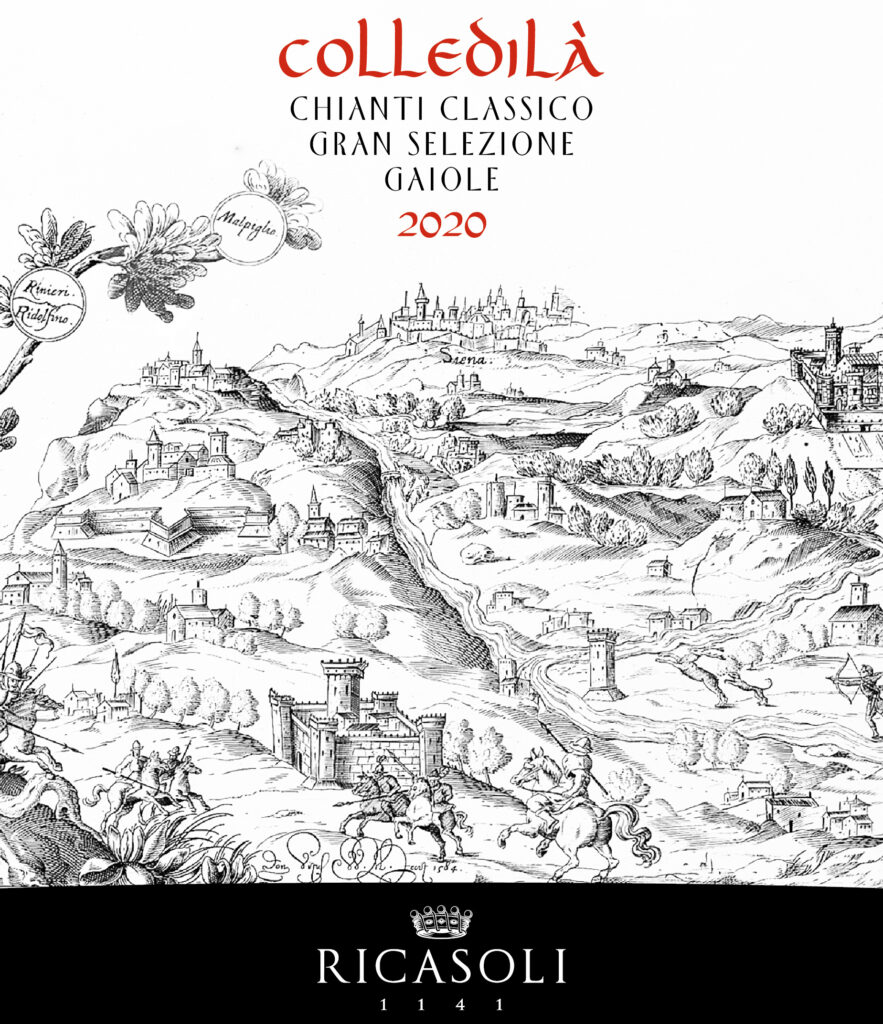

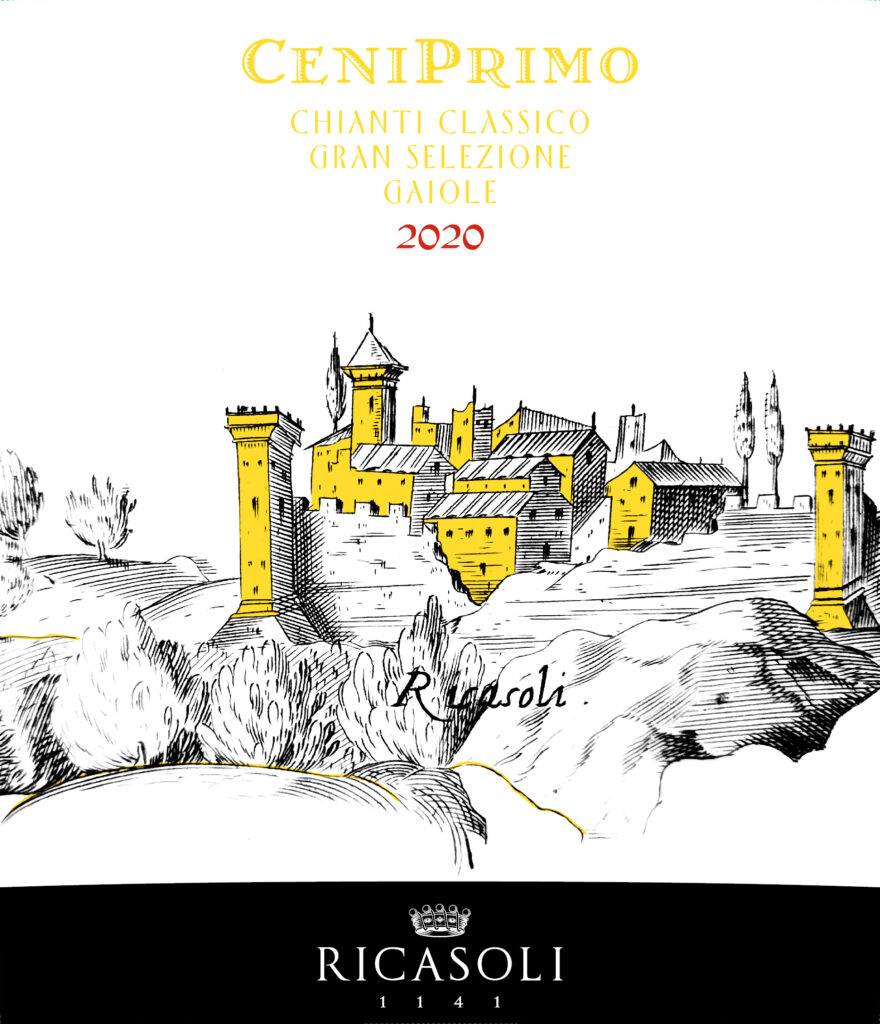

As is already known, the history of the Ricasoli family dates back to ancient times: Geremia, the Lombard who is presumed to be the progenitor, was certainly in Chianti in the 11th century. However, it is the year 1141 that marks the starting point, documented in a public deed preserved in the family archive, which confirms the Ricasoli family’s feudal sovereignty over Brolio. Among the ancient documents preserved in the castle, there is a valuable print from 1584 depicting the Ricasoli family tree, beginning with Geremia and then branching out over five centuries with his descendants. As well as displaying a myriad of names, medallions, coats of arms, and scrolls, it is almost a geographical map, set in the lands of Brolio with its hills and castles, farmhouses, cultivated slopes, and many place names that still exist today in Chianti Classico and the Upper Valdarno, mostly locations where the family’s properties were located. The tree dominates the centre of a Chianti landscape inhabited by wild animals – raptors, hoopoes, snakes, a peacock, a weasel – representing the fauna that still lives in the Chianti forests today.

The world depicted in 1584 was a complex one, not easily decipherable to inexperienced eyes, but some details are now more visible thanks to five labels of some of Ricasoli’s finest wines: Merlot Casalferro, Chardonnay Torricella, and the three Sangiovese crus Colledilà, Roncicone, and CeniPrimo.

The label of Casalferro portrays the flowering branch of a cherry tree around which a raptor hovers, and a flowering branch is also chosen for Torricella, but this time a bird with a long, curved beak, perhaps a curlew, is perched on it, a bird common in central Italy. The juxtaposition could represent the fusion of the beauty and strength of wild nature. And then the three crus: Colledilà is recognizable for the succession of hills dotted with towers and castles, suggesting that the vineyard from which this wine originates lies beyond. CeniPrimo tells the story of the castle as it must have appeared at the end of the 16th century, with the various buildings not yet joined by the large brick facade commissioned by Bettino Ricasoli. Finally, Roncicone tells us about what must have been a not uncommon occurrence in ancient times: a battle between knights in armour with lances, perhaps a reference to warrior art and its important role in the history of the Ricasoli family.

With the obvious exception of this last tale, these are all glimpses from an ancient world that can still be found in Brolio today. Here, the intention has been to blend significant agricultural activity with respect for the beauty and purity of the landscape and nature. Thus, olive groves and rows of vines have found their space alongside the incomparable nature that makes Chianti Classico truly unique.